Cult Friction

By John Cook

Radar Magazine

17 March 2008

[This important article is no longer available online. It is reproduced here as is for research purposes only. All the pictures and embedded videos on the right-hand side were parts of the original article.]

After an embarrassing string of high-profile defection and leaked videos, Scientology is under attack from a faceless cabal of online activists. Has America's most controversial religion finally met its match?By John Cook This article is from the April issue of Radar Magazine. For a risk-free issue, click here. Clearwater is prepared for its enemies. It's a warm, if overcast, Saturday in February, but all the storefronts lining the sidewalks of this sleepy town on the Gulf Coast of Florida are shuttered. The streets are mostly barren, and at the sight of strangers, the few passersby quicken their pace and avert their eyes. Outwardly, Clearwater has all the hallmarks of an unexceptional beach community—there's a Starbucks on the corner, and new construction projects dot the shoreline. But today the cranes are still and the scaffolding is empty. No one is lining up for lattes. Everyone, it seems, has disappeared. "There's one!" says Patricia Greenway, my guide, as we drive past a dark-haired woman in black slacks and a short-sleeve white shirt. When she notices us eyeballing her through the car window, she raises her hand like a scandalized starlet confronting the paparazzi. "See—she's hiding her face," Greenway says quietly, sounding like the host of an Animal Planet safari special. "They feel that if they're exposed to entheta, they'll lose their bridge." Their "bridge" is the "Bridge to Total Freedom," the path to enlightenment, levitation, time travel, and all-around invincibility peddled by L. Ron Hubbard under the name Scientology. "Entheta" is us. The enemy. Ever since Hubbard, the portly flame-haired naval enthusiast, accomplished liar, pulp fiction writer, and unlikely cult leader, came ashore here in 1975 after leading his flock on an eight-year sea voyage throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, Clearwater has been known as the "spiritual mecca" of Scientology. Members call it Flag Land Base. Beginning with its purchase of the Fort Harrison Hotel that year, the Church has methodically acquired most of downtown Clearwater, save for the library and the courthouse, amassing nearly 1.7 million square feet of office and residential space and turning the city center into a virtual Scientology campus. More than 1,200 Church staff members, and somewhere between 5,000 and 12,000 Scientologists—including Kirstie Alley (who purchased her home from Lisa Marie Presley)—live and work here. Which is exceedingly creepy, especially when they're nowhere to be found. Even so, I am skeptical when Greenway and her associate, Peter Alexander, both outspoken critics of Scientology, hesitate to get out of the car and walk around. What could really happen to us? The sidewalk is still ostensibly public property. Alexander, a soft-spoken former vice president of Universal Studios who now lives near Clearwater, attained the Church's second-highest level of spiritual awakening, OT VII, or Operating Thetan level seven, before he defected in 1997. At one point, Alexander says, he was so consumed with Scientology that he carried around a Church-issued beeper that alerted him whenever his minders decided he required counseling. Greenway, a no-nonsense blonde with a pack-a-day voice and an easy laugh, was never a Scientologist. Alexander hired her in the mid-'90s at his architectural design firm, which at the time was run using Hubbard's principles; she resisted the workplace pressure to join Scientology and eventually convinced Alexander to leave the Church. They both joined the board of the Lisa McPherson Trust—a now-defunct anti-Scientology organization that battled the Church in Clearwater for years—and made a feature-length film called The Profit about a megalomaniacal leader named L. Conrad Powers who founds the Church of Scientific Spiritualism. Greenway and Alexander have steered clear of downtown Clearwater for several months and fear that if they're spotted in the area, the Church will unleash private investigators on them (as they claim it has in the past), and that a new wave of troubling phone calls and attempts to meddle with their business will commence. This strikes me as paranoid. Eventually, we park the car and get out. Alexander points to a Greek-columned stone building that once housed the town bank. It is now the headquarters of the Office of Special Affairs, the Church's public relations arm and current incarnation of the Guardian Office, which was the epicenter of the black-bag hijinks for which Scientology is famous—infiltrating the Department of Justice, hatching schemes (which were never fully realized) to blackmail critics, bugging IRS offices, and so forth. A discreetly posted security camera peeks out from atop the building. "They've got 110 cameras downtown," Alexander says. "Just wait." Within minutes, a paunchy middle-age Latino man with a pencil-thin mustache, wearing khakis and a white golf shirt, emerges from the adjoining parking lot. He walks silently to a spot a few feet away from us, points a digital camera, and begins snapping our picture. I say hello. He says nothing. I ask him if he's a member of the Church. He stares, grim-faced, at the camera's LCD screen. Alexander and Greenway are casual; they've been through this before. As we continue down the sidewalk, a bus with tinted windows passes by. Greenway explains that it's a Scientology bus. The Church leaders don't trust the staff to own cars, she says, and they don't want them walking around with entheta, either. Greenway points across the street. The venetian blinds in the storefront opposite have been opened to reveal an office with at least half a dozen people inside. One of them, a clean-cut young man, is standing by the window, pointing a video camera, and slowly pivoting to keep us in the frame as we make our way down Cleveland Street. The Scientologists are monitoring their enemies. And they are expecting more to come. |

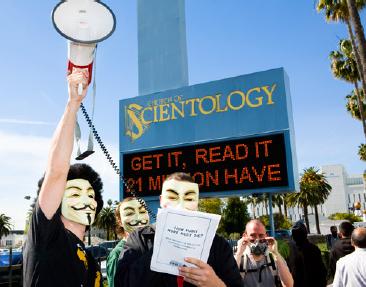

Masked hackers have declared war on Scientology. Could the celebrity-friendly religion be in its final days? (Photo: Sam Comen) |

|

| It's been a bad couple of months for

the Church of Scientology. In December, German

authorities took a significant step toward outlawing the

group, announcing that they "do not consider Scientology

an organization that is compatible with the

constitution." In January, St. Martin's Press published

Andrew Morton's Tom Cruise: An Unauthorized Biography,

which painted a scathing portrait of the actor's chosen

religion as a money-mad, fascist mind-control sect led

by Cruise's closest friend, David Miscavige, a

gun-loving high-school dropout with a Napoleon complex

who runs his religion like a paramilitary group.

Morton's book kicked off yet another blistering round of

bad PR for the image-obsessed Church, with headlines

about its efforts to draw in Katie Holmes, allegations

that Cruise functions as the Church's second-in-command,

and the far-fetched belief among some Scientology

"fanatics" that Suri Cruise was actually sired using

Hubbard's frozen sperm. It debuted at number one on the

New York Times best-seller list. Then came the video. You've probably seen it by now—leaked footage of Tom Cruise accepting the Church's Freedom Medal of Valor award at a 2004 gathering of the International Association of Scientologists. Slickly produced, with the theme from Mission: Impossible pumping along in the background, the clip features a manic Cruise exhorting his co-religionists to commit themselves to the cause. "Being a Scientologist, when you drive past an accident, it's not like anyone else," he says. "As you drive past, you know you have to do something about it. Because you're the only one who can help." |

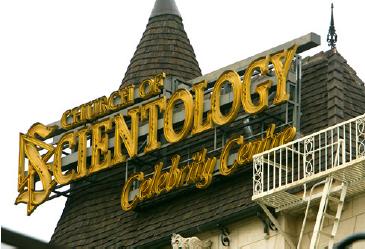

HOTEL CALIFORNIA Scientology's Celebrity Centre in Los Angeles. One of the sites of Anonymous' February 10, 2008, protests (Photo: Getty Images) |

|

| The Tom Cruise video first appeared on

YouTube on January 14, the day before Morton's biography

went on sale. (According to one longtime critic of

Scientology who is in contact with other anti-cult

activists, the leak was purposefully timed to coincide

with the book's release.) It was up for one day before

the Church forced YouTube to take it down, citing

copyright infringement. The clumsy attempt at censorship

angered many on the Web, including the Manhattan media

site Gawker, which obtained its own copy and continues

to host the video despite the threat of a lawsuit. At

press time, the footage had been viewed more than 2.7

million times. Then came Anonymous. On January 21, a video titled "Message to Scientology" appeared on YouTube. A brilliant work of agitprop, the video (embedded below) features a monotone, computer-generated voice speaking in staccato against a mesmerizing backdrop of gathering clouds. The message, which bears quoting at length, is ominous: "Hello, Scientology. We are Anonymous. Over the years, we have been watching you. Your campaigns of misinformation, suppression of dissent, your litigious nature: All of these things have caught our eye. With the leakage of your latest propaganda video into mainstream circulation, the extent of your malign influence over those who have come to trust you has been made clear to us. Anonymous has therefore decided that your organization should be destroyed. ... We are Anonymous. We are legion. We do not forgive. We do not forget. Expect us." |

"Tom Cruise Scientology Video - ( Original UNCUT )" |

|

| Within hours of the video's posting,

all hell broke loose. Almost immediately, the Church's

main website, scientology.org, went down under a

distributed denial of service attack, a classic hacker

technique that overwhelms a target's website with

phantom user traffic until it crashes. Scientology

offices worldwide were flooded with prank phone calls

and so-called black faxes—pages upon pages of blank

black pages—tying up their phone lines and emptying ink

cartridges. Dozens of proprietary Church

documents—videos, lectures, and course materials worth

hundreds of thousands of dollars in Scientology's

pay-to-pray scheme—began showing up on YouTube,

BitTorrent, and countless websites. Anonymous is the catchall term for an amorphous group of online activists-slash-hackers-slash-pranksters-slash-dadaists organized loosely around two online message boards, 4chan.org and 711chan.org. Anons, as they call themselves, are steeped in the anarchic and exceptionally juvenile culture of the Internet, and function as something like online yippies. The lolcats meme, for example—a series of inexplicably funny pictures of cats with comically misspelled captions like, "I can has cheezburger?"—first emerged on the 4chan boards, and its members have claimed responsibility for a long list of feats, including taking down white nationalist websites and stealing the passwords to 72,000 MySpace pages. Anonymous managed to disrupt the Scientology website for three days. And in a show of force—and a surprising departure from its previous, Internet-focused projects—it also dispatched legions of real live protesters to Scientology facilities around the world for coordinated pickets. Add to that the recent defections of several prominent Church members, including David Miscavige's own niece, Jenna Miscavige Hill—who is openly attacking her uncle and the Church—and Mike Rinder, the Church's former chief spokesman and public face, and you can see why the folks in Clearwater are wary of outsiders. "It's looking like the perfect storm," says Dave Touretzky, a research professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University and a longtime critic of the Church. "I just can't believe what's happened over the last six months. It's all falling apart for Scientology now. We're looking at the end times for them." |

"Message to Scientology" |

|

| Scientology, of course, has always

thrived when it's under attack. Hubbard was keen to make

sure that its enemies, whether real or imagined, loomed

large in the lives of his adherents. He railed against

"the forces of evil [who] have launched their lies and

sought, by whatever twisted means, to check and destroy

Scientology"—whether they be IRS agents, psychiatrists,

or reporters, whom he dubbed "merchants of chaos." A

pillar of the Church's theology is the existence of

"suppressive persons," who must be avoided, or

"handled," in the Church's euphemistic jargon. In 1967,

Hubbard promulgated what he called the "fair game"

policy, whereby anyone judged to be an antagonist "may

be deprived of property or injured [and] tricked, sued

or lied to, or destroyed." (He later withdrew it, citing "bad PR.") Miscavige has chosen his own aggressive, protomilitant style, pumping up Scientology troops with talk of an "assault on planetary suppression" and the "global obliteration" of psychiatry, Scientology's bête noire. In keeping with Hubbard's fair game dictate, every time Scientology has been attacked, it has quickly struck back, which is what makes the current barrage against the Church so remarkable. Not long ago, anyone brave enough to publicly criticize the organization suffered dearly. Paulette Cooper, an investigative journalist whose 1971 exposé, The Scandal of Scientology, was the first mainstream book to criticize the Church, found herself subjected to what she described as a 15-year campaign of harassment. Scientologists covertly infiltrated her life, befriended her, and, an FBI agent later told her, framed her by using stationery with her fingerprints on it to send bomb threats to the Church. Branded a lunatic, she became suicidal, lost her boyfriend, and was down to 83 pounds when a 1977 FBI raid on Scientology offices in L.A. and Washington, D.C., turned up documents indicating she had been the target of "Operation Freakout"—a coordinated campaign to get her "incarcerated in a mental institution or jail, or at least to hit her so hard that she drops her attacks." Fourteen years later, after writer Richard Behar wrote a blistering cover story for Time headlined "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power," the Church unsuccessfully sued the magazine for $416 million and sicced six private investigators on Behar himself, obtaining his phone records and credit reports, and digging into his personal life. Likewise, former Scientologists who have spoken out have found themselves cut off from their families and worse. Alexander says his clients have received calls from people claiming that he ripped them off. He believes the calls were placed by Church members. As recently as February, according to Miscavige's estranged niece, a reporter for a British tabloid received a vaguely threatening phone call after interviewing her. The reporter had contacted the Church's press office seeking a response to Hill's claims that the religion tears families apart. Shortly thereafter, he received a call from a stranger asking if his mother knew that he was working on a story about Hill. The caller then recited the writer's mother's home address. Soon after, the story was killed. The journalist, a freelancer whom Radar has agreed not to name, says the story never ran because it lacked a celebrity angle. But he acknowledges that he received a troubling call and that his status as a self-employed reporter without the backing of a newspaper made it difficult to ignore. "If it weren't little old me, I wouldn't blink," he says. "But I have blinked, and there's not much that can be done about it." Few expect the hackers behind Anonymous to blink. In fact, rarely has an opponent of Scientology so gleefully played into the Church's paranoia and xenophobia. "It's not against their people or religion," says one Anonymous member who, predictably, declined to offer his identity. "We respect the right for them to believe what they want. We oppose their lawsuits and their bully tactics. Every religion goes through its stages of infancy. The Catholics had the Crusades, but for the first time in history, the common people have enough power to stop Scientology before it gets to that." Given Anonymous' decentralized nature, it's difficult to gauge the individual motives of its members. Literally anyone with a computer can "join." And it's not just hacker nihilists: doctors, lawyers, and professors are involved, they claim. "Anonymous," says a member who calls herself Sarah, "is a collective group of individuals with no leader, who do anything they can and want." A few days after Anonymous' "Message to Scientology" appeared on YouTube, powder-filled envelopes arrived at 19 Los Angeles–area Scientology facilities. The powder was harmless, but the FBI was called in to investigate. Anons interviewed by Radar disavowed the mailings and suggested the envelopes were sent by Scientologists themselves to discredit Anonymous—a tactic the Church had used against Paulette Cooper—and claimed that, as a free-form public movement, members have no control over every action taken in their name. Another wayward attack, according to "Sarah," involved someone faxing hundreds of pages with only the word "nigger" printed on them over and over again, to a number mistakenly believed to be affiliated with the Church. She regrets that, but says she's helped "successfully stop a lot of other people who had really stupid plans." The Church has denounced Anonymous as a "cyber-terrorist group" committing "hate crimes" and accused them of "bomb threats, death threats, and threats to burn down Church buildings." "The Church can confirm that appropriate law enforcement authorities are investigating the criminal acts of Anonymous," Scientology spokeswoman Karin Pouw wrote in a 10-page response to Radar's questions. "[Anonymous] will not disrupt the Church's normal activities of serving its parishioners and the community." (Click here to read the church's entire response in PDF form.) In a sign that they were more than just a passing Internet fad, Anonymous soon graduated from pulling pranks just for the "lulz"—anonyspeak for shits and giggles—to real-life, up close and personal activism. February 10 is the birthday of Lisa McPherson, the 36-year-old Scientologist who died from dehydration in Clearwater in 1995 while in the Church's care. She was allegedly in the midst of a psychotic breakdown, and the Church was reluctant to hospitalize her for fear that she would be treated by a psychiatrist. McPherson's death sparked a round of back-and-forth litigation and galvanized anti-Scientology groups. On what would have been her 49th birthday, Anonymous scheduled protests in front of Scientology facilities in 100 cities worldwide. They planned to wear V for Vendetta Guy Fawkes masks, hand out leaflets, and carry signs. According to Anonymous, 6,000 people showed up around the world. My first visit to Clearwater's eerily deserted downtown was on February 9, the day before the planned protest. |

FREEDOM FIGHTERS Anonymous' tagline: "Because none of us is as cruel as all of us" (Photo: Sam Comen) |

|

| Invariably, former Scientologists do

the same thing when they first leave the Church: They

log onto the Internet and start searching. "Members of

the general public know more about Scientology than

decades-long members do," says Chuck Beatty, a 27-year

veteran who worked for Author Services, Inc., the

powerful Scientology organization that manages Hubbard's

copyrights. As a rule, Scientologists are forbidden from

exposing themselves to any of the dozens of websites—xenu.net,

chief among them—devoted to exposing the Church's sordid

past and nefarious nature. While much of the information

has been available on the Internet for years, you once

had to actively seek it out. Interest in the Tom Cruise

video and media coverage of the Anonymous campaign has

pushed this information out in front of a mass online

audience, reinforcing the view that Scientology is a

cult and cutting into its recruitment efforts.

"Celebrities are gaining them exposure and ridicule,"

says Beatty, "but they're not gaining them members." "Robert Vaughn Young once said the Internet is going to be Scientology's Waterloo," says frequent Scientology critic and journalist Mark Ebner, referring to a high-level defector. "And he was right." Scientology's outlandish creation myth is a closely held secret within the organization—learning about it prior to reaching OT III is said to cause mental retardation or, by some accounts, death. But for potential recruits, it is a simple matter of Googling—or watching South Park—to learn that Hubbard believed an interstellar overlord named Xenu killed billions of beings in an attempt to thwart galactic overpopulation 75 million years ago. Their souls, Hubbard taught, infest Earth-goers and can only be removed through a hybrid of counseling and interrogation known as auditing, using an E-meter, or crude lie detector. Faced with an increasingly skeptical public here at home, former members say, the Church has begun to target its recruitment efforts at communities statistically less likely to have Web access. In particular, it has stepped up its efforts in Central America, where, according to remarks made by Mike Rinder at a Scientology gathering in 2004, the first lady of Honduras is a convert. Critics point out that much of the anti-Scientology material available online has yet to be translated into Spanish, making Spanish-speakers an easier sell. The Church has also set its sights on African Americans, opening up a center in Harlem in 2003 and making a strong play for Hollywood supercouple Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith. At a 2006 gathering, Miscavige spoke glowingly of Kimora Lee Simmons's efforts to distribute a personalized edition of Hubbard's The Way to Happiness, featuring her image on the cover, to schoolkids in New Jersey. (Simmons's rep denied she was a Scientologist after video of Miscavige's speech became public. Watch the video below. Miscavige lauds Simmons' contributions to the church at 6:15.) |

MAGIC KINGDOM Saint Hill Manor in East Grinstead, the home of L. Ron Hubbard (Photo: Getty Images) |

|

| Even as Scientology comes under assault

from outside forces, it is also, say former members,

bleeding from within. "I see more and more people

leaving and willing to speak," says Tory Christman, who

worked in the Office of Special Affairs for 20 years and

says she spent more than $200,000 on Scientology courses

before dropping out in 2000. Christman left—or "blew,"

in Scientology parlance—because she has epilepsy and

wasn't permitted to take medication for it; psychiatric

and neurological drugs are a serious no-no. But after

two decades of working her way up the Bridge, she was

forced to confront the fact that even L. Ron Hubbard

could not cure epilepsy. "At the top ranks, there's a very high blow rate," says Beatty. "They can't take it anymore." Indeed, Scientology faces an inherent conundrum: Adherents are ushered up the Bridge with specific promises that they will be able to leave their bodies at will, stop time, read minds, and never succumb to illness. As long as there's another level to rise to, former Scientologists say, it's easy enough to convince yourself that your magical powers are just around the corner (even if they were supposed to have already materialized). "I got in it because I thought the out-of-body experience was real," says Beatty. "And after 20 years, I found out, it's not. But by the time you've gotten there, you've dumped a couple hundred thousand dollars, or like me, 20 years of your life into it. You don't want to give up. It's a group fantasy." To keep that fantasy, and the attendant revenue stream, going, the Church has had to come up with new ways to dangle advancements beyond OT VIII—ostensibly the highest level you can reach, according to Hubbard—without seeming too craven. In 1995, Miscavige announced what he called "the golden age of tech," which was essentially a claim that Scientology's auditors had been doing everything all wrong. "We just discovered a treasure trove of L. Ron Hubbard," Miscavige said, meaning that everyone needed to do their courses over. And pay for them, naturally. But the coup de grâce of Scientology's campaign to keep its members motivated and their wallets open is a massive 380,000-square-foot Mediterranean Revival structure, occupying a whole block in Clearwater across from the Fort Harrison Hotel, known as the Super Power Building. Though the Church broke ground on the building a decade ago, and almost everything has been flawlessly in place on the exterior since 2004, it is still not completed. According to the Church's website, the Super Power Building will contain 889 rooms on six floors, a dining room that can serve 1,400 people, facilities for 1,200 staffers and 1,600 "parishioners," five miles of carpet, and 180 miles of electrical wiring. The Church has announced and ignored innumerable completion dates; it now says it expects the building to open in mid-2008. |

"Scientology advocates violence against psychiatry" |

|

| Some former Scientologists attribute

the delay—for which the Church has been receiving daily

fines of $250 from the city—to the Church's fund-raising

prowess. Donna Shannon, a former member who donated a

total of $50,000 toward the construction of the

facility, says that as long as the Church can appeal to

members for donations, ostensibly to help finance the

building, it will remain incomplete.

But others say that the Church is still perfecting the secret training regimen the structure was intended to house—the super power rundown, a course that will give Scientologists, well, superpowers. The building's amenities will include an antigravity simulator; a human-size gyroscope to teach students how to orient their bodies; television screens that move around, rapidly flashing images to drill members on how to perceive subliminal images; a facility for producing a variety of odors to train the olfactory sense; oversize furniture to help determine spacial relationships; and a circular track to run around, over and over again. The rundown is a new course that even OT VIII's will want to pay for. Matt Feshbach, a billionaire hedge fund manager and devoted Scientologist, is one of the lucky few who has experienced a pilot program of the super power rundown. Apparently, it works. "I'm not dependent on my physical body to perceive things," he told the St. Petersburg Times in 2006, adding that he had already saved the life of a young boy with his new abilities by stopping him from running into the street. One Scientologist who has apparently forsaken his superpowers is Mike Rinder, formerly head of the Office of Special Affairs and chief spokesman for Scientology. In what many ex-members describe as a significant black eye for the Church, Rinder blew last summer and now lives in Williamsburg, Virginia. Rinder was one of the most powerful men in the organization; it was his Australian baritone that proclaimed on ABC's 20/20 in 1998: "Every few thousand years a man comes along who is so extraordinary he changes the course of history, and L. Ron Hubbard is one of those men." "Rinder leaving Scientology is like Goebbels leaving the Nazis," says Beatty, who speculates that Rinder couldn't put up with Miscavige any longer. Miscavige is notorious, former Scientologists say, for mistreating and screaming at underlings. (Church spokeswoman Karin Pouw "categorically denies" any allegation that Miscavige has mistreated anyone: "Mr. Miscavige is a beloved and respected leader. Your question is offensive in the extreme." As for Rinder's current status in the Church, she says, "Religious membership is personal." Efforts to reach Rinder through another ex-Scientologist who has been in contact with him were unsuccessful.) Miscavige, for his part, is having trouble keeping his own family in the Church, let alone his henchmen. In 2000, his brother Ron and Ron's wife, Bitty, left Gold Base—a formerly top-secret facility roughly 90 miles east of Los Angeles that serves as the Church's international headquarters—for Virginia. Both Miscavige brothers were raised in the Church by their father, a Polish-born musician who joined Scientology while living in Philadelphia. (It was David, however, who caught Hubbard's eye and served as his assistant from the age of 14.) Ron Miscavige has remained silent since his defection. He did not return Radar's phone calls or e-mails. But his daughter, Jenna Miscavige Hill—David's niece—caused an uproar in February by writing an open letter to Pouw denouncing the Church's policy of "disconnection," in which followers are forced to forgo contact with anyone declared a suppressive person, even family members. Pouw had previously issued a statement in response to Morton's book, claiming that disconnection is "the opposite of what the Church believes and practices." That, Hill says, is not true. "If they're so arrogant that they can completely lie when people know the truth, they're not going to change," she says. "I felt like I had to say something." Hill says the Church tried to keep her from talking to her parents from 2000, when they left the Church (she was 16 at the time), until 2005, when she followed suit. Moreover, she describes a harrowing childhood as a third-generation Scientologist, in which, even as a small child, her life was heavily regimented and she was required to do manual labor. From the age of six, Hill lived at Castile Canyon Ranch, a private Scientology-run boarding school near Hemet, California, about 20 miles from Gold Base, where her parents lived and worked as Scientology staff. (Scientology is divided into "staff" and "public" members; many of the staff are under total control of the Scientology hierarchy and receive courses for free or at a discount, while public members like Greta Van Susteren and Tom Cruise are free to do as they please and pay for courses.) "I saw my parents once a week," Hill says. Along with 80 other children of staff at Gold Base, she says, she woke up every morning at 6:30, put on a uniform, and cleaned her room until inspection at 7 a.m. Then she worked handing out vitamins to other kids. After that, she says, "We'd do rock hauling and demolition, dig trenches, plant trees." When the grueling physical chores were done, she would study academics and Scientology materials until 9:30 p.m. "It's kind of weird when you're six or seven years old to have to study until 9:30 at night," she says. "We had units, we had to call people Sir, we did close-order drilling. It was run like a military organization." Hill has fond memories of her uncle David from her time at Gold Base. Her family often spent Christmas holidays with Miscavige, she says, and he would take her to movies and even once to a hockey game. Things changed when, at age 12, she was drafted into the Sea Org, an elite cadre of Scientology staff. Hill recalls, "I went to Clearwater to visit some friends, and they said, 'Here's your uniform. You're in the Sea Org.' After that, it wasn't the same. He wasn't my uncle anymore. He was Sir. He's like God there." In Clearwater, Sea Org recruits sign a contract promising one billion years of service to the organization; in the event of death, inductees are allowed 20 years to "grow the body" after they are reincarnated, at which point they are expected to report for duty. They are also required to fill out an exhaustive questionnaire bearing this quote from Hubbard: "You can't be shot for what you have done, you can only be shot for what you haven't told us." The Church asks whether applicants have ever been affiliated with the CIA or Mossad or have ever held a security clearance, and requires them to fill out a detailed sexual history, including "any perversions" and "who, what was done, and how often—be as complete as you can." During her four years in Clearwater, Hill says she went to school once a week. She spent the rest of her time studying Scientology and performing administrative work. Her parents stayed back at Gold Base, and Hill says she saw her mother "once for about a half-hour" and her father "three times for at most a half-hour each time" over those four years. |

THEY ARE LEGION Members of Anonymous take to the streets (Photo: Sam Comen) |

|

| Nicholai Allen, a classmate of Hill's

at the ranch, corroborates her story. "I was seven when

my mom took a job at Gold Base," he says. "She had no

idea that she wouldn't be living with me when she got

there—she wasn't given a choice. Almost immediately I

was put to work cleaning bathrooms, harvesting

vegetables, and building rock walls." One day, when Hill was 16, the local head of the Religious Technology Center, the body in charge of enforcing Church doctrine, told her she needed a "sec check," or security check—a lengthy inquest using an E-meter. "I was interrogated eight hours a day for six weeks," she says. "I couldn't talk to my friends. I had to put on a grubby uniform, and when I wasn't being interrogated, I had to clean the bathroom. When I slept, there was always someone guarding the room." She was never told why. After six weeks, she was flown to L.A. When she arrived, she was told to go to the Office of Special Affairs' boardroom, where she found Mike Rinder and Marty Rathbun, Miscavige's second-in-command. "[Rinder] said, 'Your parents are leaving, and you're going with them.'" The sec check was standard operating procedure for anyone—even a 16-year-old—leaving the Church. "They wanted to know if I had any evil intentions toward my uncle," Hill says. "They wanted to find out if I was going to speak out." To the contrary, Hill chose the Church over her family. "I was brainwashed, so I didn't want to go," Hill says. She convinced Rinder, Rathbun, and her parents to let her stay on in L.A. and remain on the staff of the Sea Org. Hill never attended school again. During her time in the L.A. Sea Org, she says, all of her parents' letters to her were intercepted, and she was forced to read and answer questions about them in the presence of Rinder. She eventually married a fellow Scientologist named Dallas. In 2005, after a particularly aggressive auditing session in which she was questioned for hours because she criticized her superiors for attempting to take away her cell phone—Hill's only mode of contact with her parents—she announced that she wanted to leave the Church. "It was after a culmination of a lifetime of things," she says, that the cell phone issue finally flipped a switch in her head. Dallas, who was more indoctrinated, took some convincing, and the couple put off the decision for a few months. Hill later found out that during that time, Rinder and other people in the Office of Special Affairs were covertly interrogating Dallas. "They were secretly talking to my husband," she says. "Mike Rinder was telling Dallas bad things about my family, [encouraging him] to reevaluate, and telling him that he wouldn't be able to talk to his parents. Not to keep Dallas, but just to fuck with me." Finally, after Dallas broke down and told Hill about the secret interrogations, the couple agreed to leave. "We went and stayed at a Travelodge," Hill says. "They showed up the next day with a U-Haul full of our stuff. The guy delivering it told Dallas, 'I'm going to do everything in my power to make sure your family disconnects from you.'" "We had no money," she says. "No credit. I didn't have a driver's license. No nothing. I was 22. There are a ton of people like me." Hill and her husband now live in San Diego. She declines to talk on the record about her current relationship with her parents, but says of her upbringing, "I wouldn't even let that happen to my dog." "Jenna Miscavige speaking out is probably the most devastating thing to happen to them so far in terms of long-term damage," says Carnegie Mellon's Dave Touretzky. "To hear that [David Miscavige's] own niece left the Church and is accusing him of breaking up her family—that's huge." Asked about Hill's account of her childhood, Pouw said: "The Church does not comment on how parents choose to educate and raise their children. Children were never forced to engage in manual labor." According to Pouw, "Facilities provided by the Church for the children of staff at [Gold Base] were nothing short of spectacular. In addition to a boarding school, facilities included swimming pools, basketball courts, football fields, baseball diamonds, and even horse stables. Citrus orchards and organic gardens, maintained by professionally trained gardeners, were also provided." "Yeah, there was a stable," Hill says bitterly in response. "And we were the ones who built the horse corral. We were the ones who hauled the horse shit every week. I rode a horse one time in the six years I was there." |

WE CAN HAZ XENU? Masked protestors (Photo: Sam Comen)

WE CAN HAZ XENU? Masked protestors (Photo: Sam Comen) |

|

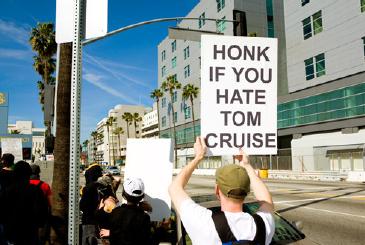

| On the morning of February 10, Lisa

McPherson's birthday, Clearwater is desolate again. A

broken car horn wails incessantly somewhere in the

distance. Anonymous begins gathering at about 11 a.m. The Church has hired nine off-duty police officers to provide security at the march; there's an air of a high-noon showdown in the offing. The assembled Anons are surprisingly diverse. One protester I spoke to gave his name as "Wesley Crusher," the youngest crew member in Star Trek: The Next Generation, but the crowd extends beyond the usual hacker suspects—there's a schoolteacher, college and high school students, even a few fraternity types. Many are dressed in suits; all have some sort of bandanna or mask covering their faces. By 1 p.m., the appointed time of the march, close to 200 people have collected at a staging area near the library. Someone pulls out a birthday cake for Lisa McPherson, and, in a surprisingly earnest moment for an Internet-based assault force, the crowd sings "Happy Birthday." Dave, the young, self-appointed leader of the group, urges restraint. "Let's not burn down any buildings," he says. "I've got to say that 'cause I know some of you all are pyros. Xenu is watching you, so be careful." The march turns out to be the largest protest against Scientology in the history of Clearwater. Old-hand anti-cult activists who come down to check it out are impressed. The signs read "Ron's gone but the con goes on" and "Honk if you hate Scientology." For the next two hours, a chorus of car horns continually blares. "I think it's great to see people protesting," says one local woman who refuses to give her name. "I work for a company that's owned by Scientologists. I just got the job for money. I didn't know it would be creepy and weird." Another local couple says they just came downtown for the afternoon, not to protest, and someone took a picture of their license plate as they parked. "We had no idea this was the epicenter of Scientology," the woman says. "Otherwise, we wouldn't have moved here." The surveillance is in full effect as I make my way around downtown; young men in short-sleeve shirts, khakis, and sunglasses seem to emerge out of nowhere to snap your picture each time you walk past a Scientology building. They don't respond to questions or acknowledge your presence, they just stare at the camera's screen. I spot one woman walking down the street carrying an L. Ron Hubbard book and ask her what she makes of the crowd chanting "Cult! Cult! Cult!" "I don't have any thoughts whatsoever," she replies curtly. The protest is peaceful, with no arrests or confrontations. According to Karin Pouw, 5,000 Scientologists were inside the Church buildings engaged in religious services without regard to the "terrorists" outside. As the picket line starts to dissolve, I make my way back to my car, down a deserted side street. I am the only one on the sidewalk. A white Japanese car drives past me; as I look over I see a blonde woman snap my picture from the passenger seat. I walk faster. Fumbling for my keys, I spot a brown car pulling out of the supermarket driveway, across from the lot where I've parked my car. The driver lifts up a digital camera, snaps a shot of me, and drives away. According to Anonymous, the protests brought out a total of 6,000 protestors in more than 100 cities worldwide, including more than 500 each in London and Los Angeles. The group insists that the campaign will continue: On March 15, Hubbard's birthday, Anonymous is organizing mock birthday parties at Scientology centers worldwide. In April, it will launch Operation Reconnection to increase awareness of the disconnection policy. Anonymous member "Sarah" says the group is also organizing a letter-writing campaign designed to take aim at the Church's nonprofit religious classification. "We're sending letters to senators and congresspeople requesting that their tax-exempt status be looked at." |

THE WEBSITE SCIENTOLOGY DOESN'T WANT YOU TO SEE A protester in Toronto promotes xenu.net, one of the Web's most prominent anti-Scientology sites (Photo: Joe Howell) |

|

| The Church of Scientology is not going

away anytime soon. It still has hundreds of millions of

dollars. It still has Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes,

assets that gave the Church, as Miscavige put it at a

recent event, "16 daily hours of nonstop ... televised

coverage and four full miles of press bringing word of

LRH technology to 42 million people a week" during the

tabloid extravaganza leading up the couple's 2006

wedding. You may have thought you were reading about

Holmes' Armani dress in Us Weekly, but that's not what

Miscavige saw: "While they may have headlined it wedding

of the century," he said, the coverage really "amounted

to an intro lecture" to Hubbard's teachings. And Scientology isn't taking Anonymous' attacks lying down: A representative told the St. Petersburg Times that the Church would work to identify the protesters that gathered in Clearwater on February 10, because "any of them could be a security risk." "Sarah" says that one of her cohorts received a text message from an unidentified number bearing the message: "If you know what's good for you, you'll stop lying about Scientology. This is your last warning." The main website used by Anonymous for planning events has been dogged by denial of service attacks for weeks. And in mid-February, a new video purporting to be from Anonymous appeared on YouTube. It threatened to blow up a Scientology building in Los Angeles. Suspicious it could be a fair game tactic, Anonymous members immediately informed the FBI that it didn't come from them. YouTube removed the video, along with the original computer-narrated manifesto. (The latter video was eventually restored; the Church denies any role in getting it taken down.) Still, the genie is out of the bottle. As Bruce Hines, a former OT VII who left the Church, says, "With all this publicity, very few people would go home after work and say, 'Oh, honey, I just found out about Scientology and I'm going to take this course.' The response would be, 'What? Are you crazy?'" Click here to view the official response from the Church of Scientology. This article is from the April issue of Radar Magazine. For a risk-free issue, click here |

FACE OFF Armed with signs and megaphones, Anonymous protesters chant "Cult! Cult! Cult!" (Photo: Sam Comen) |